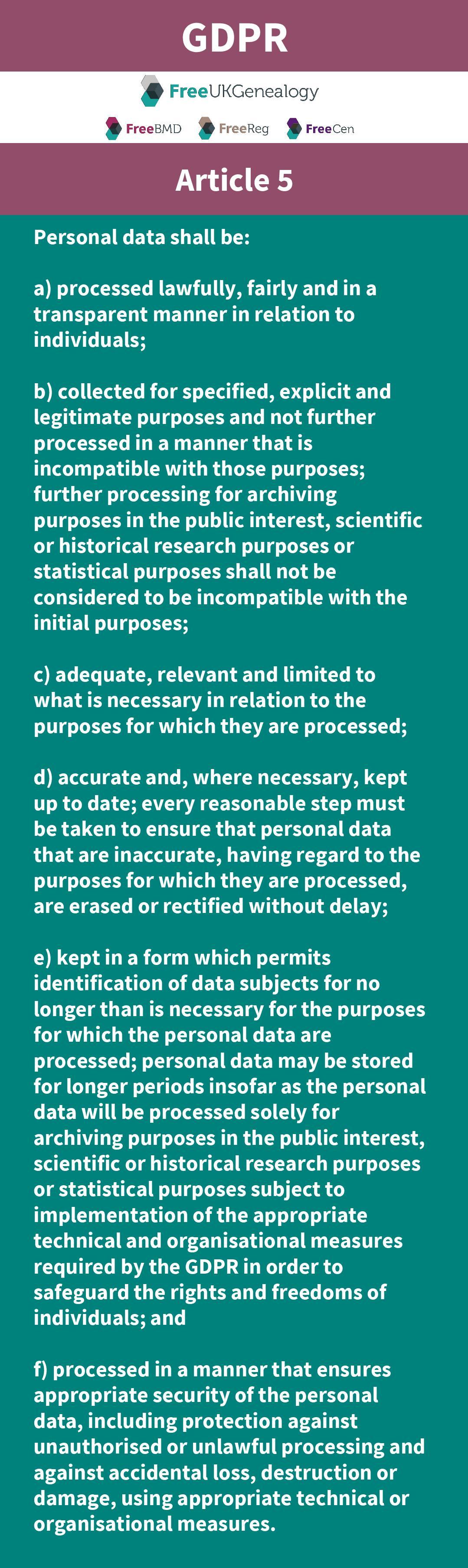

The General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) comes into force on the 25th of May 2018. Designed to augment existing Data Protection rules, the principles as set out in Article 5 show clear requirements that all personal data held by anyone must be stringently and transparently collected, stored, processed and preserved or removed, and will result in heavy fines for breaches and failure to comply.

Genealogy services that store and process data are having to review and strengthen their procedures; for example WikiTree are removing DNA test information on living non-members. Family historians may understandably have questions about what the GDPR means for genealogical research… will we still be able to order birth, marriage and death certificates for living people? Will the harsh rules and measures lead to the destruction of records that could be of future genealogical interest? What about other personal data that FreeUKGEN holds?

Records on Free UK Genealogy websites

While many of the records on our websites are about dead people, some Record Subjects are living people, and thus regulated by GDPR. Very occasionally, a record focussed on a dead person will contain information about living persons - for example, a burial record can state someone is the widow, or widower, of a named living person.

We collect and process publically available register and census information including personal data about a Record Subject’s birth, baptism or other similar entry into a religious body, marriage and marital status, occupation (e.g. ‘groom’s occupation’), gender, age and other personal data as is recorded in historical documents. We consider it is legitimate to process this information for research purposes, including statistical and historical purposes. Further, many of the records we process provide public access to official documents, including indices of Birth and Marriage, and registrations of marriage these are likely to be, additionally, covered in an exemption.

Destruction of records

Article 5 states that “...further processing for archiving purposes in the public interest, scientific or historical research purposes or statistical purposes shall not be considered to be incompatible with the initial purposes”. (Article 5)

In the recent ‘Windrush immigrants’ case, a former Home Office employee reported that landing cards of people who have lived in the UK for many years, which were used to establish their status were deliberately destroyed by the Home Office in 2010. Responding to the claim, the Home Office admitted that records were destroyed but claimed that this was necessary to comply with the Data Protection Act (DPA). However, the Board of Trade had transferred comparable historical records to the National Archive (BT 26 Inwards Passenger Lists 1878 to 1960), and government departments continue to do this. For example the surviving aliens' registration cards for the London area as recently as 1991, which survived by accident, have been transferred, and are now open records.You can find them on the National Archive here.

It is a real concern that the fear of incurring large fines may drive organisations to destroy business records that could be a rich source of genealogical information. It is easy to see how managers and Data Protection Officers may believe that destroying documents holding personal data removes any risk of mishandling. We have seen such a case on social media involving a local funeral director with 45 years worth of records. Worried that their small business doesn’t have the time, money or expertise for further processing, they arranged for the historic records to be shredded.

It is clear that the GDPR highlights the importance of effective records management and should help drive the case for investing in new information management technologies and programmes. Businesses could donate records that are no longer needed by them (e.g. no longer covered by a contract) which nevertheless have research value to an appropriate research institution, such as a local archive, or transfer to a business archive.

Record Disposal Policies of local councils often include provision to ensure that records of potential historic interest or research value are identified and transferred to their Archive Service. This would have to be done with the agreement of the Archive Manager, going through the formal accession or deposition process that must take into account already strained resources such as storage space and staff to manage and maintain the records.

The ARA are arguing for “clear language in any UK and Irish implementing legislation that ‘all archiving purposes are in the public interest’ and therefore all archives have a clear legal basis to exist and do their invaluable work.”

Other personal data that is held by Free UK Genealogy

Free UK Genealogy holds data for a number of other reasons that are permitted by GDPR (and its predecessors):

Contract: e.g. we have (unwritten) contracts with our volunteers - in order that they can transcribe, we have to send them images or links to images, and in order to do that we have to hold and process their email addresses.

Legal: e.g. some people, very kindly, permit us to claim Gift Aid on their donations. We have a legal obligation to pass their names and addresses on to HMRC, and hold and process this information to do this.

Legitimate interests: we include information about our legitimate interests in our forthcoming revision of privacy information. We hold, for example, the names and email addresses of people who have contacted us using our contact form, in order to be able to reply to them.

We don’t have any ‘vital’ interests (data held/processed to save lives) and we don’t (at the moment) carry out ‘public tasks’ (if a public body delegated tasks to us, we would do).

Consent: where we have no contract, legal or legitimate interest, we need to ask for consent to hold and process data (for example, in the past we have sent invitations to test new features, notices of forthcoming meetings, and similar to our newsletter mailing list. While we hold and process the personal data of who has signed up for the newsletter as part of a contract (they ticked a box saying they wanted the newsletter), they didn’t sign up for additional emails - so we have asked that they give us explicit consent for each additional kind of mailing. Consent is the ‘last straw’ of legitimate data holding and processing.